Lately, I’ve thought that we should be more public about our game design goals. If we’re open about what we’re trying to design and why, you can better know if our games are right for you. So I'm writing about one of our most important and challenging game design goals–creating board games that appeal to serious and casual gamers.

Why is it hard to appeal to gamers and non-gamers?

The members of most family and friend groups have varied tolerances for strategy and competition when it comes to board games. When strategy lovers want to play games with more casual players, those games shouldn’t be too much for the casual players or too little for the strategy-lovers.

It’s tough to design such games.

At a minimum, we should strike a balance between the two needs. But ideally, we don’t compromise between the two needs and we satisfy them both. Gamers and non-gamers want different experiences, and for both to enjoy a game, they must almost perceive it in different ways:

- The non-gamer wants to feel competitive without having to strategize too deeply.

- The gamer wants to see impactful opportunities for deeper strategizing, despite simple rules.

This is the problem we’re trying to solve–how to create games that meet both of these needs.

How do we create games that gamers and non-gamers will enjoy?

We’re currently taking two approaches to this. First, we’re trying to create subtleties in our games that satisfy two heuristics:

- Gamers can see those subtleties, while non-gamers either can’t see them or don’t feel a need to dwell on them.

- The subtleties don’t imbalance the games too much in favor of players who see them, but they’re still consequential.

We think this is possible because skill and randomness in games are independently adjustable variables. Game designer Richard Garfield has illustrated this point with a toy example. I'll illustrate it with a game example.

Consider the games Chess and RandoChess. RandoChess is just like Chess, except when the game ends, you roll a die. If the result is 1-4, the player who would have won under normal Chess rules wins. Otherwise, the other player wins.

Both games have the same amount of skill. All the tactics and strategies that give a player an edge in Chess also give them an edge in RandoChess. But the size of the edge is smaller in RandoChess. In other words, Chess is a high-skill, high-edge game, and RandoChess is a high-skill, low-edge game.

This proves it’s possible to make a game where players can exercise a lot of skill without imbalancing the outcome too much in the skilled players’ favor. Of course, RandoChess is also a bad game.

The challenge is to make a high-skill, low-edge game that feels right to both casual and strategic players.

How we pursue this goal at Underdog Games

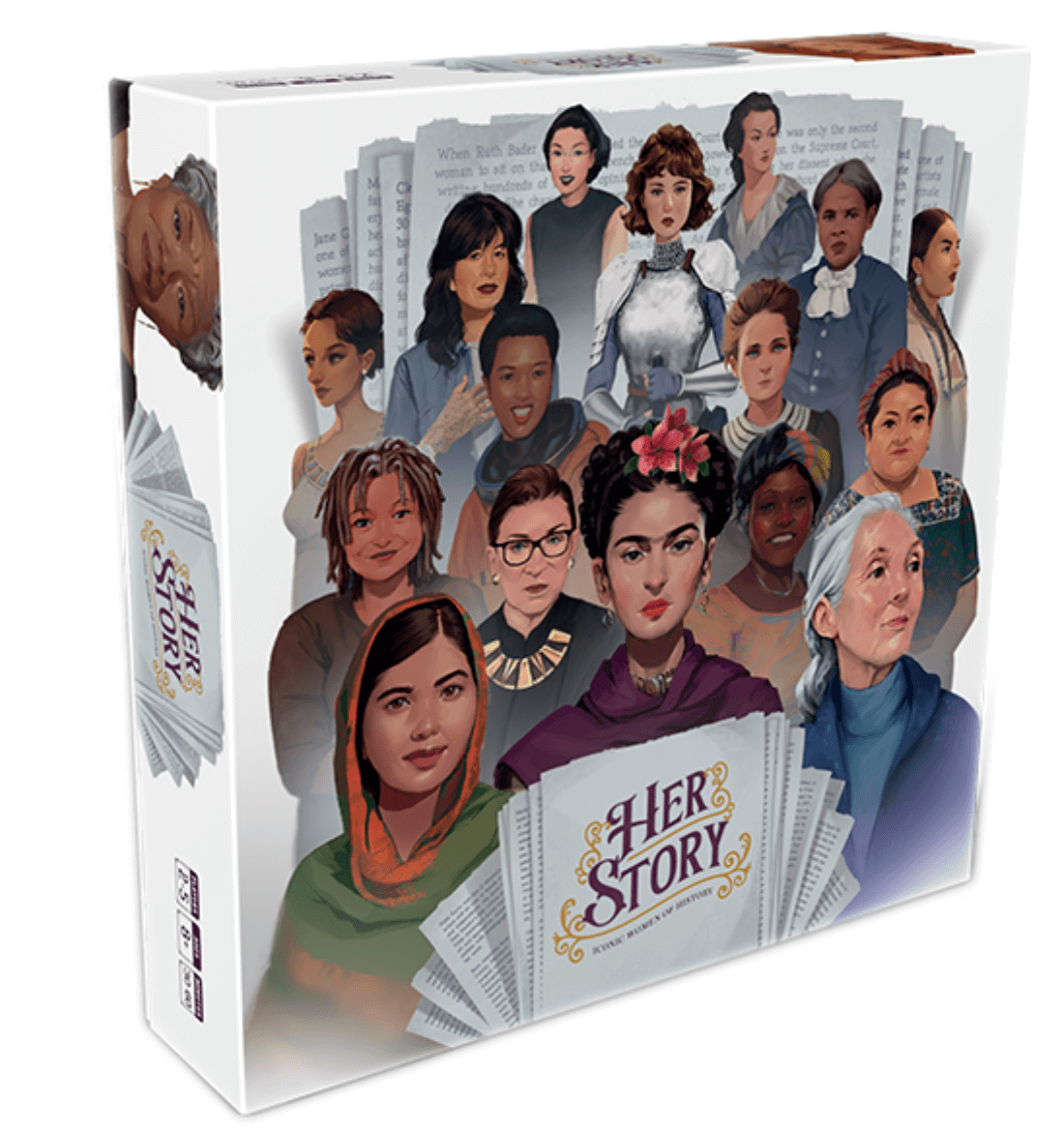

I’ll illustrate how we try to make games that feel right to all players with our most recent attempt: our upcoming game HerStory.

HerStory is an engine-building game built on top of a set-collecting game. Engine building refers to mechanisms where, over the course of a game, players build increasingly complex systems for generating points or resources. You don’t need to know what engine building or set collecting is to play a game, except set collection is pretty easy for non-gamers to understand, while engine-building is harder.

When designing HerStory, we tried to create a balance between the set collection and the engine building. For example, if you only pay attention to the set collection, you may not win, but if you collect sets well, you’ll have a chance. But to maximize your winning chances, you must develop an understanding of the engine building and how it integrates with the set collection, which is more complicated.

We won’t know if we’ve succeeded in appealing to gamers and non-gamers until we hear from HerStory customers, but in playtests, non-gamers tended to focus more on the set collection and gamers more on the engine-building.

A second approach to appealing to all game players

Along with using a balanced approach to set collecting and engine building, we're pursuing another solution–games where turns start simple and then get incrementally more complex, turn by turn.

We suspect that by incrementally acclimating non-gamers to complexity, it’s less likely to intimidate them. We’re especially interested in engine building for this reason, because it already has this feature. This is why HerStory is partly an engine-building game, albeit a very light one.

Follow Nick on Twitter for fantastic insight on game design, the board game industry, and so much more.

To get more insights on the Underdog game design process, check out this article I wrote about how fatherhood made me a better game designer.